I began to read books about kayaking adventure, and on kayaking technique, in my teenage years. Nowadays, many of the books, both old and new, on my shelves are about travel exploration, and often relate in some way to kayaking, sailing, mountaineering, or the arctic. Inevitably one adventure leads to another, just as one explorer inspires others. The stories in these books frequently overlap, or cross reference the adventures of others. I enjoy following the links; those little cross-references that spring up unexpectedly between them. In that way my collection has grown and diversified.

|

| The northern Lights begin to glow over northern Labrador |

I am not alone in my delight. My friend Kevin Mansell, from Jersey in the Channel Islands, has a similarly diverse and prized collection, although most likely fuller than mine.

In New Zealand, I have seen Paul Caffyn's enviable library. Both Mansell and Caffynl are personally familiar with adventure,

embarking on early groundbreaking kayak expeditions, and both also collect kayaking

related stories among other subjects. Caffyn has written several books. But it

was seeing a photo of Kevin’s bookshelves that made me question my hoarding. Sure,

I refer to them all the time in research for writing. Is that why I surround

myself with books in my tiny office?

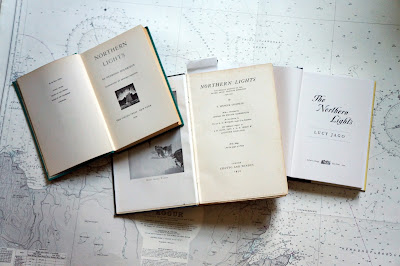

To ponder this question, I pulled a book from the shelf. The explorer Gino Watkins having recently cropped up in conversation, the book I chose was “Northern lights”. I knew where it was located, but if I had asked someone else to find it, they might have pulled any one of three books from the shelves, each with a similar title.

|

| Three books with similar titles |

“Northern Lights”, published in 1932, recounts the British Arctic air route expedition from 1930 to 1931, Written by Spencer Chapman, it is a revealing book about British Arctic exploration in Greenland, illustrated with black and white photographs. It offers a fascinating insight into their use of small, lightweight, Moth biplanes, fitted as needed with floats or skis, which helped with their mapping. It was in a Gypsy Moth that my father later learned to fly.

|

| Northern Lights: about Greenland |

|

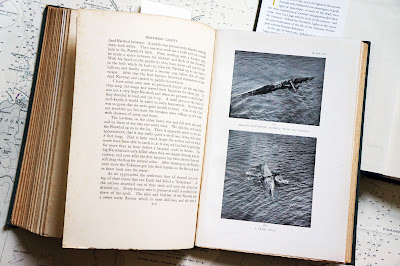

| Chapter XII about The Art of Kayaking |

During their stay in Greenland, Gino Watkins' team learned from the Inuit

how to fish from the ice, hunt from kayaks, and handle sled dogs. As a kayaker,

I was delighted to find a whole illustrated chapter titled “The Art of Kayaking”,

which title, coincidentally, I chose as the title for my

recent book on kayaking technique. Chapman’s chapter begins with the

focus on hunting seals.

|

| The Greenland expedition used Moth aircraft for aerial surveys |

The second book, also “Northern Lights”, was written

by Desmond Holdridge and published in 1939. It narrates the story of a 1925 sailing

trip to northernmost Labrador. What inspired Holdridge to write about his

adventure thirteen years later was the book he had just read. That was “Northernmost

Labrador, mapped from the air” by Alexander Forbes, about his exploration and

mapping from the air around the entrance to Hudson Strait, a book also on my

shelf not gathering dust.

|

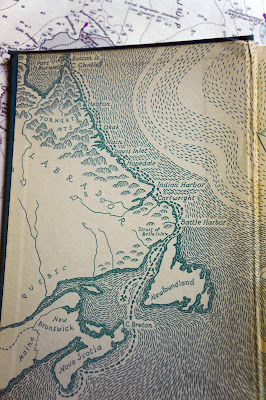

| Northern Lights, about Labrador |

|

| Inside cover maps Labrador sailing route |

In 1925 Holdridge, with two companions, sailed a small

schooner from Nova Scotia to Killiniq Island at

the northernmost tip of Labrador, (now part of Nunavut) and most of the way

back, before sinking. His account describes many of the Inuit settlements that

at that time populated Labrador, describing the people and the nature of the

coast. The story, wonderfully descriptive and easy to read, is a treasure trove

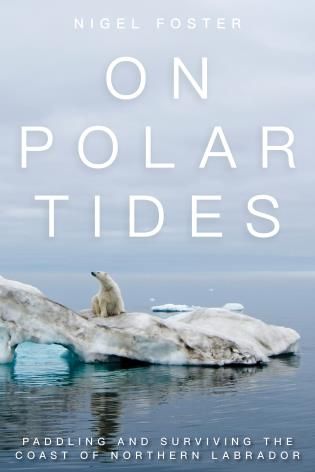

of information about Labrador, a precious resource to me. I describe my own,

much later adventures to the northern tip of Labrador, by kayak in the book: On Polar Tides

|

| Northern Lights over Labrador from the book On Polar Tides |

One of the wonders of traveling in that part of Labrador is the nightly spectacle of the aurora borealis; the northern lights, after which these books were named. Vast dancing curtains of green and red lights play across the backdrop of starry skies. Having seen the spectacle, who would not yearn to learn more? So, on target, the third book, titled "The Northern Lights” was written by Lucy Jago and published in 2001.

|

| The Northern Lights, about the Norwegian scientist who unlocked the mystery of the auroras. |

It is the story of the man who unlocked the secrets of the

Aurora borealis. Jago’s research revealed the fascinating life of Norwegian

scientist, and inventor, Kristian Birkeland who

lived from 1867 to 1917. He successfully predicted that plasma was present

everywhere in space, and he was the first to explain the nature and behavior of

the solar wind. His theory of the cause of the auroras was proven to be correct

in 1967 after a probe was sent into space. Of course, much more has been

learned about space and the universe since 1917. Brian Greene’s books, also on

my shelf, offer more recent perspectives. But his subject matter leads me into

other wormholes.

|

| Birkeland set up arctic stations to study the northern lights |

Each of these three “Northern Lights” volumes is precious to me, but collectively they are even more so for the ways they knit themselves together, while also pointing me off in new directions. The questions they inspired led me down myriad paths into other books that now grace my shelves. All are interconnected by that invisible web. I need only open one book to recall the links to many of the others.

I owe so much to books, I offer my thanks to those who take the time to write them.